After three entire days of relaxing I am beginning to feel more calm. I admit to spending a lot of time thinking about the same things that fill my brain at other times. Things like wondering about how music fits into people’s lives.

But in this calm, my usual answers of how important music is to me seem stronger. My need for others to understand this about me diminishes as I spend time reading about, thinking about, listening to and playing music.

God bless the interwebs.

I have been reading in Gardiner’s Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven. He often sends me scurrying to find books, music scores and recordings. Yesterday I read the passage where he points out that Handel and Bach both created interesting compositions at the age of twenty-two. I had listened to the Bach composition, Christ lag in todesbanden, the day before yesterday. Then I was able to listen to Handel’s Dixit Dominus. With both pieces I kept the score in front of me as I listened.

Gardiner can hear the future of both composer’s style in these two pieces.

“… even at this stage there are pointers to the divergent future preoccupations of these two giants: love, fury, loyalty and power (Handel); life, death, God and eternity (Bach).”

While Bach was in Germany (where he spent his entire life), Handel was in Rome.

Calling Handel a dramatist in the making, Gardiner says:

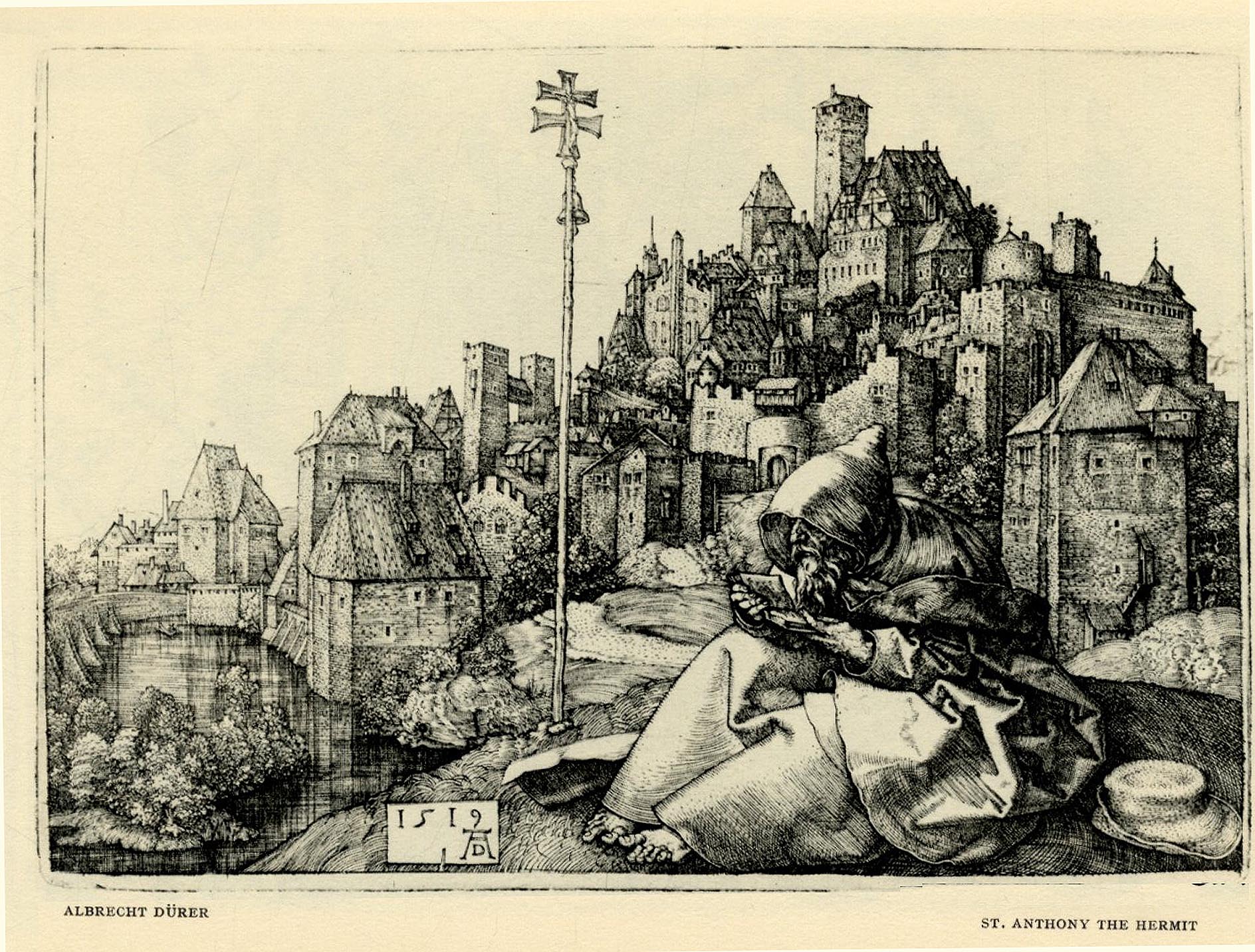

“Where Bach is yoked to Luther, Handel, decidedly more of a man of the world even at this stage, shows us why he was so drawn to Italy, responding, like Dürer and Schütz before him, and Goethe later on, to her landscape, her art in all its vitality and vivid colors, and of course, her music.”

I was amused to see Handel at a young age already using the same climbing long soprano lines that one associates with the Hallelujah chorus.

Gardiner thinks that both Bach and Luther looked death in the eye.

“Precociously, he [Bach] seems to have learnt how the colossal force of faith embodied and enacted in music could deprive death of its powers to terrify, as though concurring with Montaigne (whom he certainly never read), ‘Let us banish the strangeness of death: let us practice it, accustom ourselves to it, never having anything so often present in our minds than death: let us always keep the image of death in our imagination—and even in full view.”

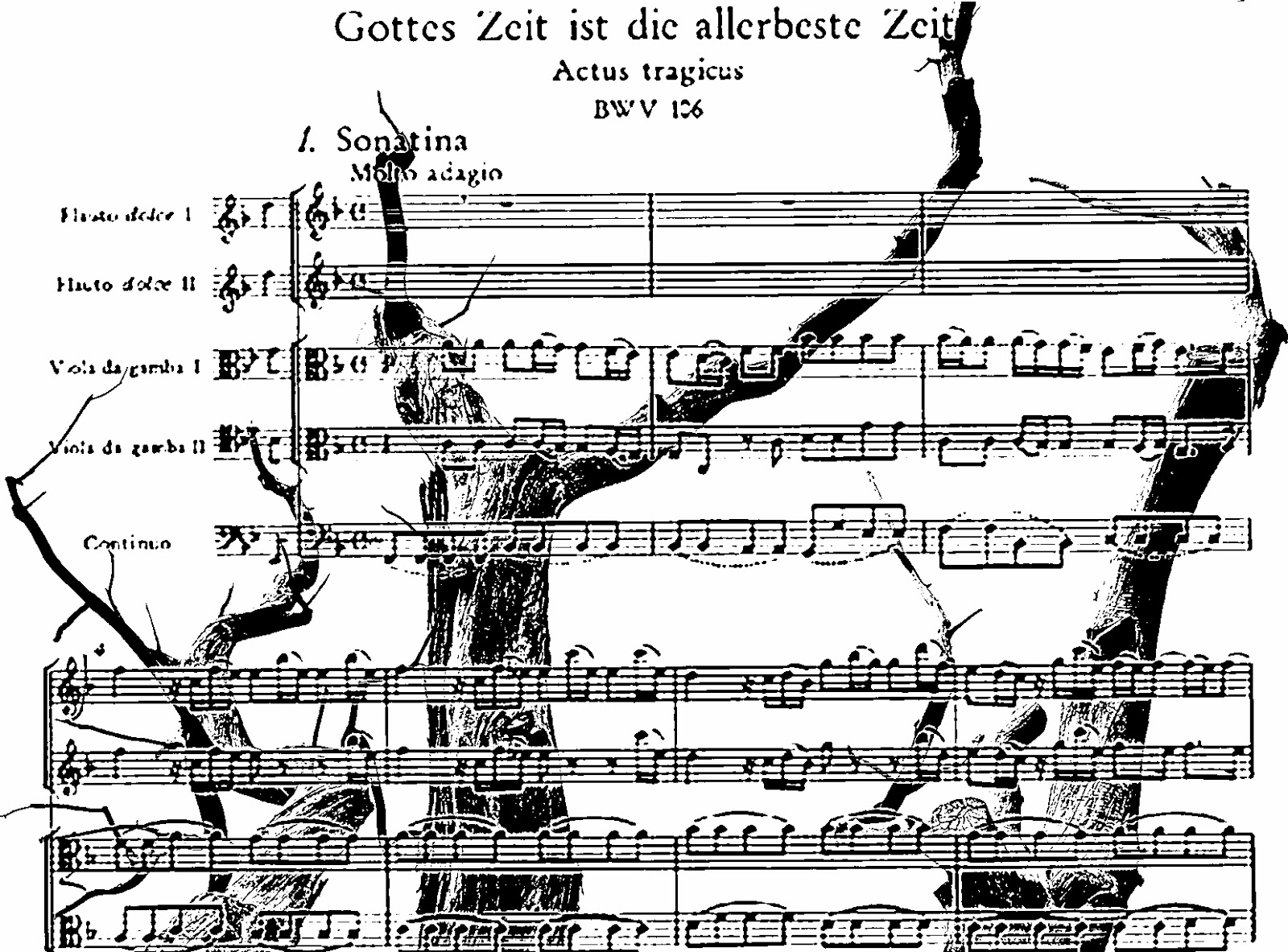

Gardiner is writing about the great Actus Tragidus (BWV 106 – Gottes Zeit ist der allerbeste Zeite – God’s time is the best time). I got up this morning and listened to this masterwork. I had never done so before. I recommend it as a work of genius but won’t belabor you with a discussion of Gardiner’s thoughts or my reactions to its structure and compositional accomplishments.

Gardiner speculates that Bach may have been thinking of the people in his life who were dead at this point. That would include his parents (buried in the cemetery next to the church where Bach was baptized – Georgenkirche in Eisenstadt), and also the sister of a friend of his (Susanne Tilesius, sister of Pastor Eilmar).

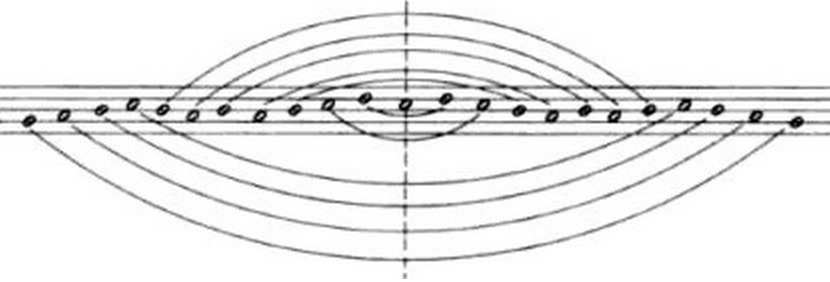

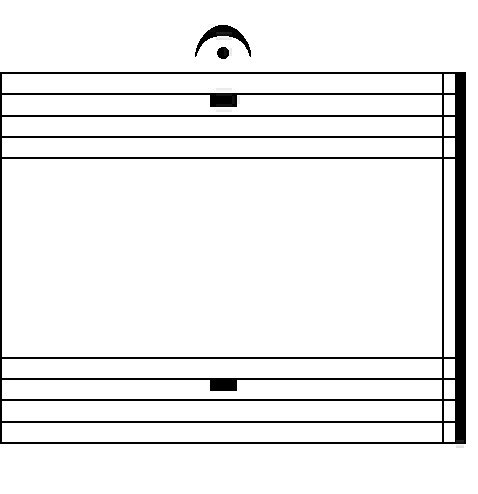

I can’t resist pointing out the clever construction of this piece with movements that correspond to each other in clever and symmetrical ways. And in the center of this comes a rest with a fermata over it.

Gardiner says “… it is up to us how we interpret …. [this] silence…. ” One interpretation would see it as an indication that death is a full stop. Another is that death is a midpoint and “the beginning of what comes after.”

Very cool.